There are plenty of infographics that will tell you just what comes out of a barrel of crude oil. And I am going to base this article on one of those since the information is largely the same across the board. But what I want to do with this article is highlight just how intertwined with oil modern life is and how difficult it’s likely to be to wean ourselves of the sticky, thick black stuff.

For reference, the article I’m using is from the Visual Capitalist (Conte, Niccolo; Sep 14, 2021) and can be found here: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/whats-made-barrel-of-oil/

In the oil industry, a barrel is the standard unit of measurement used when it comes, not only to the buying and selling of oil, but from the standard size of the barrel used to contain and trnasport oil that’s been dug out the ground. The capacity of a barrel is 42 gallons (190.9 litres).

From that, I’ll get the big one out the way. Petrol/Gasoline comprises of 42.7% of the output (17.9 gallons/81.37 litres) and that’s used to largely power private vehicles of which there are roughly 1.5billion worldwide. Of that, 78% (Statista – https://www.statista.com/statistics/827460/global-car-sales-by-fuel-technology/) are powered by petrol.

Next, diesel. 27.4% (11.5 gallons/52.31 litres) . This is the fuel of industry and goes to power trucks, lorries, diggers, mining equipement, back-up generators, etc. For private vehicles, 14% use diesel.

Aviation uses 5.8% (2.44 gallons/11.07 litres) of the content of a barrel of oil in the creation of jet fuel of which there are three mains types:

- Jet A is primarily used in the United States. This fuel is developed to be heavier with a higher flash point and freezing point than standard kerosene.

- Jet A1 is the most used jet fuel worldwide. Jet A1 has a lower freezing point (-47° C) than Jet A (-40° C) so it is especially suitable for international travel through varying climates. This type of fuel also contains static dissipater additives that decrease static charges that form during movement. Despite the differences between Jet A and Jet A1, flight operators use both fuels interchangeably.

- Jet B is the most common alternative to the jet fuel and AVGAS, primarily used in civil aviation. Jet B has a uniquely low freezing point of -76° C, making it useful in extremely cold areas.

(Source – National Aviation Academy: https://www.naa.edu/aviation-fuel/)

After aviation, Heavy Fuel takes 5% of the barrel (2.1 gallons/9.54 litres). This is a much cheaper fuel as it’s less refined and therefore thicker compared to the previously mentioned fuels. As a result of being less refined, it emits more black carbon than the other fuels when burned. This is the fuel of choice for the shipping industry.

So, 80.9% of the barrel is used for fuelling vehicles that are vital to our everyday lives. But what about the remaining 19.1%?

Well, 4% (1.68 gallons/7.64 litres) goes into the very thing that land vehicles and aircraft need to move around effectively. Asphalt. Or, as we call it here in the UK, bitumen. It’s the sticky black glue that holds the rock/sand combo together that creates roads, runways, pavements, car parks and even tennis courts.

Moving down, we get to Light Fuel which takes up 3% of the barrel (1.26 gallons/5.73 litres). This sulfur-free oil is used in places where low levels of pollution is acceptable i.e. indoors powering heaters, powering farm and mining equipment, providing back-up power to nuclear power plants. Given these uses, it works in Arctic weather and is therefore well suited to working in demanding conditions.

Hydrocarbon gas liquids take up 2% (0.84 gallons/3.82 litres) of the remaining barrel. These compounds are the likes of butane and propane which go into fuelling lighters, camping stoves, barbecues and water heating systems. They are also used in other non-fuel based compunds like plastic, solvents, paint and synthetic rubber,

The final 10.1% (4.24gallons/19.28 litres) gives us a small plethora of compounds from residual fuels to petrochemical feedstocks and other materials like wax and plastics. Various petroleum products are created which are then used to blend in with and create finished fuel products.

So, that’s what’s in a barrel of oil, but let’s scale that up. Per day this year (Statista, 2022), the world has consumed, on average, 99.4million barrels of oil.

To let you see what that looks like:

- 1.78billion gallons of petrol

- 1.14billion gallons of diesel

- 242.5million gallons of aviation fuel

- 208.7million gallons of Heavy Fuel

- 166.9million gallons of Asphalt

- 125.2million gallons of Light Fuel

- 83.5million Hydrocarbon gas liquids

- 421.5million gallons of other compounds

That’s daily. I won’t bother with an annual breakdown as it’s clear already a great amount of oil is used to run our lives. Well, the Developed World’s lives anyway.

But the big question is how to move away from a substance that’s been so damned instrumental in being the answer to so many problems, whilst being instrumental in creating so many problems of its own?

I’m not going to claim I have any answers. Merely suggestions. These are far too big and require international cooperation on levels rarely seen throughout human history.

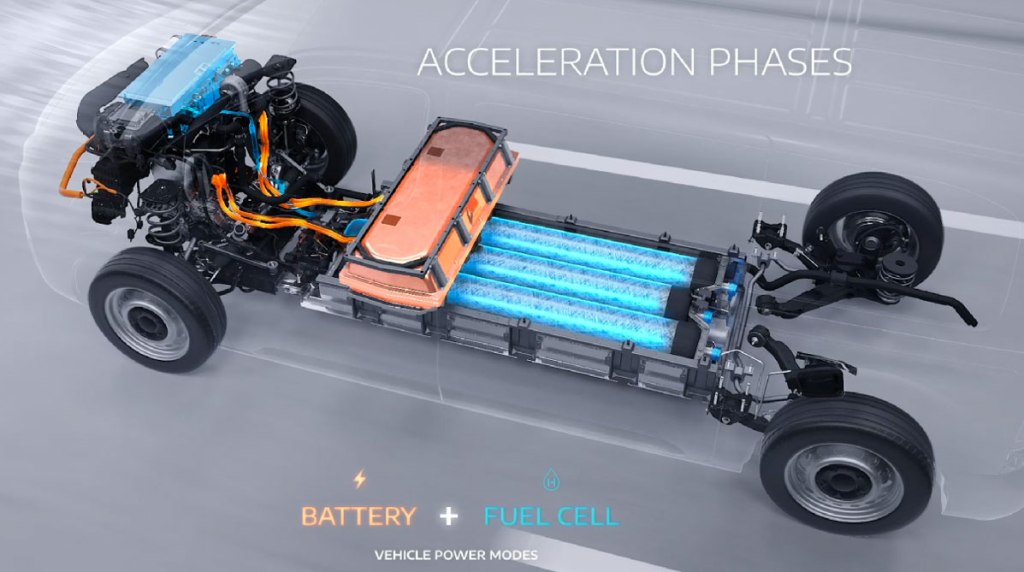

Firstly, we need to come to sensible arrangements regarding mixed use of alternatives. The rechargeable battery used in electric cars is not, as a I see it, a long-term solution. It’s excellent for making loads of money in the short-term for manufacturers, but the issue with them is they cannot be reused as they, as with all recharagable batteries currently, have a finite number of charging cycles. Once the battery can no longer hold a charge, it’s sent to landfill like everything else as the materials used to make the battery have been exhausted.

And those materials are not environmentally friendly either. Nickel Manganese cobalt, Lithium-ion, Neodyium, Nickel Metal Hydride, Lithium Sulphur and Lead-Acid are used in full electric and hybrid vehicles. These minerals are rare and need dug out the ground so a lot of mining is involved meaning more Light Fuel and diesel being burned. In the case of Lithium-ion, the main refineries are in China which are powered by coal. As for Cobalt, this is extracted in South Africa where child labour is widely used so there’s a humanitarian element to this as well.

Then there’s Nickel. The mining of ore kicks up plumes of sulphur dioxide and toxic metal dust that contains the Nickel itself along with Copper, Cobalt and Chromium. The bulk of the mining is done in Australia, Canada, Indonesia, the Philippines, Russia and South Africa (https://www.ifpenergiesnouvelles.com/article/nickel-energy-transition-why-it-called-devils-metal). The processes are largely powered by coal and most of the companies will not agree or adhere to any kind of standards that will reduce the environmental impact of the activity. Having said that, it’s been reported the Philippines has, as of 2017, closed down 17 Nickel mines out of environmental concerns.

And these are some of the issues for battery production for electric cars. Once you’ve gathered these materials and made the battery, you now have an item which takes up a third of the weight of the vehicle. And given a lot of electric cars are over 2 tonnes, the battery weighs more than the largest engine fitted to a production car in the 21st Century so far. That engine being the quad-turbo W16 found in the Bugatti Chiron which weighs 400kg. However, with the battery being the floor, it can aid with handling but creates the engineering problem of the battery making a significant contribution to the inertia that needs to be overcome to get the vehicle moving in the first place.

So, what to do? There’s been talk of an air and aluminium battery which, if it works, would remove the need for mining rare and resource-intensive materials. The battery itself has high energy density to low weight (8.1 kWh kg−1 to 2.71 g cm−3) and, in theory, could provide an electric car with 1,000 miles of range. Sounds great but the technology is still in devlopment and not likely to come to market until the 2030’s at the earliest. Realistically, it’ll be the 2050’s before production-ready cars are on the road.

We then have hydrogen as an alternative fuel source but its problem is its size. We are dealing with the most abundant element in the known universe but it’s so small, it sticks to other elements like oxygen and carbon. In order to extract the hydrogen, we have to cool gas down to well below freezing to make it a liquid thereby not only making the extraction process easier but it prevents the hydrogen from escaping as its density has been increased from the reduction in temperature. That in itself requires a lot of energy. Once the hydrogen molecules have been detached, you then have to send the liquid hydrogen along pipes which will result in loss of hydrogen and cost more in energy to keep the pipes cold. Those pipes will lead to depots where hydrogen can be loaded on to trucks to then be distributed to filling stations. All of which requires energy and will likely lead to more loss. In principle, hydrogen is an ideal solution for powering vehicles, particularly in fuel cell form, but the problem is…everything else.

Ford did make a prototype Focus in the early 2000’s which had an on-board hydrogen generator. It could take any water source, purify it then use the clean water to make hydrogen to power the car. Weirdly, this never came to market and I can’t find any reference to it since I saw it in Auto Express. Odd, that.

Other forms of engine are in the works. The Omega hydrogen rotary engine (https://www.carthrottle.com/post/this-pistonless-25000rpm-capable-engine-shows-ice-could-have-a-future/)weighing a measly 16kg but with an output of 160hp and and 170 lb ft of torque is ideal for a regular family car. And it’s modular so you can add engines dependant on your requirements. What’s the drawback? There are no seals and the components, whilst few, operate within very tight tolerances and require pressure generation to be at least ten times that of an ordinary combustion engine to overcome the lack of seals. And it revs to 25,000rpm which is more than the V10 era F1 cars that revved to 20,000rpm. In a domestic vehicle, the precision engineering will have to be there to ensure reliability. The average person doesn’t want to be changing engines after one drive unlike F1.

Solar powered cars were tried in the late 90’s and haven’t really been heard of since and for good reason. The technology still isn’t efficient enough to harness the heaps of energy the Sun sends our way every hour.

Note that I’ve been talking about how to best power cars. What about everything else? As I see it, the car is a test bed for perfecting new technologies since everything else is much bigger, more demanding and operates in far more rigourous conditions where much higher standards are required. Imagine a battery-powered freighter using current techology? It wouldn’t get out of the port before needing a charge. And planes? Forget it. In 2021, Rolls-Royce managed to fly their electric single-seater aircraft, ‘Spirit of Innovation’, on electric power at 345mph for over 3kms. That’s nothing. Yes, it’s early days but serious innovations need done before we can talk about passenger aircraft running on anything not based on oil. It’s all well me saying that whilst I sit here not involved in the slightest, but I think industries are spreading themselves too thin by investigating too many alternatives and not having a clear plan on how to achieve the highly ambitious ‘net zero’ targets by 2050.

Nuclear ships have been in use by the military for decades. This technology has been proven in military marine applications so why not for commercial ships? Well, it was demonstrated in 1959 with the NS Savannah (https://www.engineering.com/story/why-are-there-no-atomic-cargo-ships) which operated safely until 1972. However, in the 70’s oil prices were low and replacing or retrofitting existing fleets with even more expensive nuclear ships or nuclear engines just wasn’t econimically viable. Oil was going for $2 a barrel which made bunker oil/Heavy Fuel dirt cheap (emphasis on dirt) back then. But cargo vessels were much smaller and carrying less goods compared to today’s supersized craft carrying record loads of goods. From an engineering and economic standpoint, nuclear would be an excellent option today for shipping companies. One nuclear craft could run for 30 years before needing to refuel meaning the companies wouldn’t have to worry about the price of fuel for a long time but it also buys them time to stockpile cash for when refuelling day comes.

Additionally, think of all the skilled people who’ve spent years working on nuclear military craft who could use their skills on a civilian boat? Not only use, but train civilian professionals in how to maintain a nuclear-powered craft. The problem? Nuclear activists that have the technical literacy of roadkill that have been successfully lobbying for over 50 years.

The big problem with electric is generation. At present, if every car in the world was electric, we’d be outsourcing pollution to the power plants that generate the electricity. That’s not the way to go. That’s a cheap and dirty trick that will allow politicians to hit their targets before leaving office.

And I’ve only covered transport so far. But within transport, we have the other oil-based products that go into the very vehicles we’re trying to wean off oil. The interiors have plastic whilst the exterior uses rubber for seals and tyres. The paint is also oil-based so just because you run an electric car doesn’t mean you’re green. You’re still heavily supporting the petrochemical industry in every other way.

And it has only been fuel that companies have been talking about. Removing our reliance on oil also means ridding ourselves of its ancillary products, otherwise we’re just kidding ourselves that we’re ‘carbon-neutral’ whilst drinking out of a reusable mug made of plastic, coated with paint and filled with hot contents created using electricity generated by a coal-powered plant. It’s like saying you’re vegan whilst wearing the oh-so-cool leather jacket you love.

Speaking of leather, vegan leather is also oil-based as it’s made from various types of plastic. Sustainable, my arse.

And then there’s industrial, economic and national politics to consider. Developing new forms of energy means depriving energy-generating countries of current revenue which will affect their political clout on the international stage. Corporations that provide materials will also be deprived on an equivalent clout meaning their attempts to lobby rival energy sources will be less effective. They won’t want that.

Just like Edison did to Tesla in the battle between DC and AC, and the oil industry did to the alcohol and steam-powered cars, you can be sure that whatever non oil-based fuel we end up using, it’ll be the least efficient and most expensive because profit always goes ahead of progress and preservation. I don’t care about all the piped up talk about ‘environment’ this, ‘clean’ that or ‘green’ over there. First and foremost, greedy individuals in positions of influence need their pockets lined because they’re selfish and do not have the planet’s interest at heart. Second, they have agendas designed to keep themselves in their positions of power and influence and will shut down anything that threatens that. Thirdly, for cleaner fuels to have any chance, you need governments and corporations from the main countries of production to get on-board and commit to investing in truly sustainable sources of energy. To do that, you have to get rid of the corrupt bureaucrats from points 1 and 2 and replace them with honest, diligent people who will do the work to hit the agreed goal.

In reality, we’re not in a fight for the planet and the future of life on it. We’re in a fight against the destructive elements of human nature and how to mitigate its impact for the future of life on this planet.